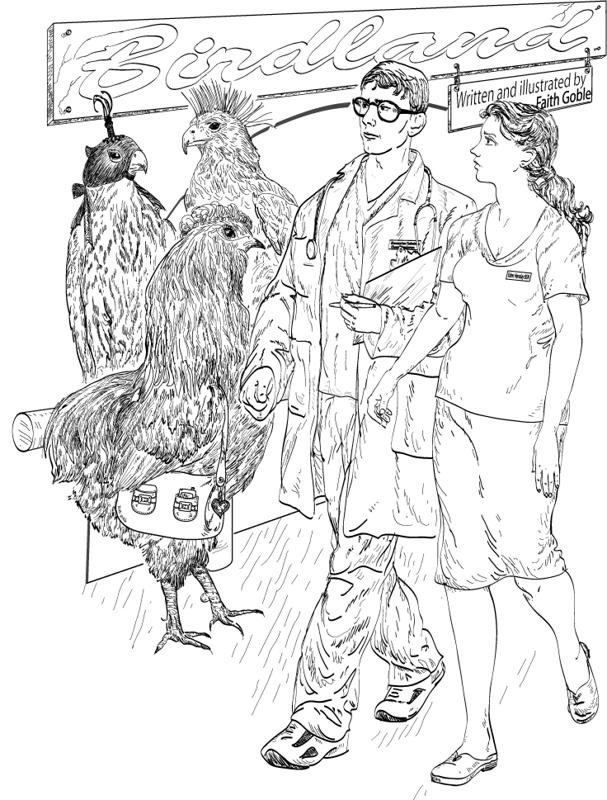

Birdlandby Faith H. Goble |

|

| Chapter 2 |

The mysterious Lodestars that have suddenly appeared in the sky have brought about an apocalypse. Michael, who has contracted a bizarre medical condition, moves to the Palace, the indoor capital city of Birdland, a nation of genetically modified, hyper-intelligent birds. In his position of technician, things go downhill fast for both Michael and civilization.

|

Curious about this abrupt change in my fortunes but happy nonetheless, I quickly gathered up my meager belongings and took the elevator up to L3, which housed offices dealing with much of the day-to-day administration and government of all of Birdland. When I reached Personnel, there were several people waiting in the anteroom, but for some reason I was ushered past them and escorted to Ms. Chickman’s office, the door of which proclaimed her as Director of 5F Labor.

Ms. Chickman was an attractive red-headed woman with a big nose. She had even bigger breasts, which, though unfettered, were amazingly round (their size was quite impressive on such a slender woman, and I was afraid she might topple over under their weight). She was scantily clad, and as she rose from her chair, she exposed pale, bare thighs.

“Have a seat, Mr. Swift. And please call me Anne.” The young woman sat down in the chair across from mine, crossing her legs and flashing her red lace underwear as she did so. “Oh, wait a minute.” She struggled up from the low chair (her tight skirt must have made rising difficult) and walked behind her desk to pick up a form-laden clipboard.

Leaning over to hand it to me, she gave me a look down her blouse at her gravity-defying and imposing ramparts, which seemed to be trying to migrate to either side of her narrow chest, perhaps to better defend her armpits. “Please fill these out, Michael. You don’t mind if I call you Michael, do you?”

She sat down across from me once again, simpered, batted her eyelashes, and offered me a cup of tea from a samovar on the table between us. “Or perhaps you’d prefer vodka.”

Things certainly were different on this level. My old supervisor had never offered me tea (which was cultivated in Birdland’s vast greenhouses). I doubted that he’d know what to do with a cup of that civilized and archaic beverage if one appeared in his grimy hand. (The denizens of the basement contented themselves with a weak and nasty home-brewed beer they made from scrounged birdseed.)

Trying to hide my surprise at the strangely gracious treatment, I thanked Director Chickman (I couldn’t bring myself to call her by her given name) and declined the offer. She seemed disappointed by my refusal, tried to press more refreshments on me, and kept attempting to engage me in conversation.

For some reason she made me uncomfortable, especially when she wanted to show me some peculiar photographs of herself. Perhaps she was simply lonely or she needed experienced service personnel a lot more than I’d have thought.

Chickman handed me an employment contract and told me I would be repairing the equipment in the nestrooms on L1, the uppermost and nicest level. She told me that I was now a TOOL (Technician [for] Ornithological Optimization, Lifestyles), First Class, and “I can always use another one of those,” she said, her enthusiasm for TOOLs apparent. Then she told me within a couple of months, I might even move up to a habitation design and planning position, a rare honor for a humanimal.

I was given commissary and cafeteria vouchers and assigned a private room (much to my surprise) in the newly renovated dormitories on L3. Finally, Chickman informed me that I’d have a half-day off a week as a first-class TOOL; she suggested I stop by for a visit when I had free time and “wanted to get anything off my chest.”

I appreciated the neighborly offer, but I was much more excited about the opportunity to visit the Palace’s renowned libraries during my afternoon off. (The birds were great believers in the value of education, even for humanimals, and many amenities and facilities were open to all.)

“Oh, one more thing!” Chickman flashed me yet another somewhat disconcerting smile and another equally disconcerting glimpse of her underwear “You need a supplementary physical before you begin work on the top levels. Here’s an order for the new humanary clinic on L3.”

* * *

The modern skilled-workers’ clinic was a revelation after the clinic on L4, well-equipped and full of shiny machines. A white-coated humanarian asked me innumerable questions (he even seemed concerned about my headaches and prescribed some pills to alleviate them), hooked me up to a number of those mysterious machines, and then x-rayed me several times. I didn’t understood the purpose or the explanations of many of the tests, but apparently my health was acceptable, and I was put to work soon thereafter.

* * *

The top level of the Palace was almost unbearably bright to eyes that had grown accustomed to the dark, close confines of the basement; and when I first stepped out of the elevator on L1, I was dazzled by the sun. It beamed through thick glass panels made without the familiar bull’s-eyes, the trademark of the glassblower’s craft.

The birds, of course, could do better; their glass was clear and flawless, the way men used to make it during the ManAges. Back home, most windows were barred or crisscrossed with boards. Only the wealthiest humans could afford glass, and it was never like this.

The air on this level was different too, fresh and sweet with fragrant life. It smelled of flowers and greenery, not of unwashed bodies as did the stagnant, fetid air of the basement below; nor of smoke, decay, and garbage as did the human city I’d left behind.

And unlike the dying city of my birth, with its ominous silences broken by sudden screams and cries, here the very air itself seemed alive, to hum almost imperceptibly with quiet industry and order. If I listened closely, I could faintly hear the ordered twitter of young birds reciting their multiplication tables from a nearby classroom; I thought of the ragged hordes of feral human children begging in the streets back home.

Besides the most exclusive private schools and nestrooms, the Palace’s top level housed expensive eateries and shops, a neighborhood library, and an art gallery featuring works by well-known five-fingered (5F) artists. It also boasted Wings of Mercy Hospital, a clinic, and a pharmacy.

L1’s large atrium was planted with dwarf fruit trees, well-trimmed berry bushes, and colorful flowers; and in its center, a fountain splashed softly. The restful, liquid sound made a pleasant counterpoint to the singing of small wild songbirds.

I quickly got into the habit of taking my lunch break in the atrium, eating my tofu- and bean-sprout sandwiches at a bench by the fountain and reading a paperback from the library for a few minutes before returning to work. One sunny afternoon I drowsily watched a pair of young lovebirds on the bench across from mine coo at each other as they pecked at a bag of sugar-coated peanuts.

My head, which had been aching all morning, began to throb, and I put down my sandwich and closed my eyes. Warmed by the sunlight filtering through the glass and soothed by the sound of the falling water, I felt my eyes grow heavier as the peaceful noises and the pain in my head seemed to slowly recede into a cottony white stillness.

When I awoke from my nap a little later, the sun didn’t seem so bright, and the lovebirds were no longer huddled lovey-dovey on their bench. I was slumped over uncomfortably, the remains of my meal beside me. I stretched and glanced at the ornate wall clock suspended above a lush bed of crane flowers; if I didn’t hurry, I’d be late getting back to work.

My headache was a little better, although I felt weak and queasy. I took one of the pills that the humanarian had prescribed for me, choked down the rest of my sandwich, and went back to work servicing the nestrooms’ air exchangers.

* * *

The level one nestrooms were warm and comfortable, with capacious perches and fresh straw covering the floors. The doors to these rooms were never bolted: Birdland had no crime to speak of (there was no shortage of necessities and amenities for any bird) and almost no antisocial behavior.

The nestrooms on the nicest levels were unoccupied in the early afternoon since the young birds were at the communal day-nests, the schools, and suet parlors; and most of their parents were working: teaching, doing research, conducting business, supervising 5F laborers, and so forth.

It was peaceful as I changed filters and checked thermostats in one of the smaller nestrooms, but I gradually became aware of a ringing sound I’d not heard for months. At first I paid it little mind, but suddenly I felt dizzy. I grabbed at a smoothly planed pine perch, the carved pins holding it in place splintering under my weight as I fell.

* * *

“Michael? Michael!” piped a shrill voice. “Are you awake, Michael?”. The voice emanated from a brilliant white blur, and as my eyes adjusted, the blur resolved into a three foot tall Sulfur-crested Cockatoo — just like I’d seen in the pulpies — perching by my side.

“What happened?” For some reason, my voice didn’t seem to be working right and my head was pounding. “What happened?” I asked again, louder this time.

The bird shifted on his perch, and his stiff flight feathers rustled as he moved. “You seem to have had a seizure, and you’ve been asleep for quite a while. You probably don’t remember much right now, but you’re okay for the time being.” He paused and seemed lost in thought for a little while. “Fortunately, we were just about ready for you anyway...”

“What do you mean?” My headache was slowly starting to subside.

“We know about your illness — the headaches you’ve been having and the seizures — and we’re very interested in your situation. As I’ve gleaned from perusing your medical history, your seizures appear to be unusually difficult to control. You seem to be a bit of a rara avis, and we could learn a great deal by studying you.”

The big white bird peered at me and puffed out his feathers a little. “You see, we’d really like to better understand seizure disorders. We’re always flying into windows, you know. Right there you’ve got plenty of head trauma that sometimes causes seizures. Then you’ve got the young birds sowing their wild oats — getting into fermented fruit, putting on silly costumes and riding around on those little bicycles and whatnot.” He shook his head, a rueful look on his face. “Lots of head injuries.

“What we find out from you can help us better understand and treat seizure disorders. And, Michael” — the cockatoo looked smug — “that’s why we’ve decided to offer you the very best in experimental treatment. We’ve been studying the results of your physical — blood tests, x-rays and the like — and we’ve come up with a groundbreaking treatment protocol.”

I couldn’t take my eyes off the exotic bird. I had rarely seen the most intelligent of the enhanced birds — the true parrots, cockatoos, and New Zealand parrots — in the flesh. The majority of the birds I’d encountered so far were passerines, near-passerines, pheasants, and raptors. There was a large group of chickens, but they spent much of their time shopping, playing bingo, participating in polls, or answering questions in bird-on-the-street interviews for the pulpies.

“As a matter of fact, Michael, we’re just now completing a therapeutic chamber designed especially for you. This chamber should shield you from the remaining Lodestars’ electromagnetic energy. For all we know, that energy might be somehow exacerbating your seizures. Additionally, the chamber will isolate you from any allergens that might be making your symptoms worse. You’ll also receive experimental drugs to mitigate your seizures.”

“Oh, okay. That sounds good... I guess.” I still felt disoriented, and I didn’t know what to think of the cockatoo’s offer. In my limited experience, the birds weren’t particularly altruistic as far as we humanimals were concerned. I supposed I didn’t have much to lose; perhaps the birds could help me, and it sounded as if they’d already made up their minds to do so.

The bird tilted his snowy head to the side, watching me. “We’ll be studying you and trying to find some answers. This is something a man with your family’s scientific background can appreciate.”

I wondered why the cockatoo would have gone to the not inconsiderable trouble of finding out about Mom and Jeff. Most records had been destroyed during the fall of humanistic civilization (they’d been burned along with the books and furniture), and I didn’t know how anyone could find out about my history unless the information had been gathered from people who’d known my family or me. “How did you know about my background... um.. sir?” I asked tentatively.

“Oh, forgive me for not introducing myself earlier. Name’s Hawk. Actually, Dr. Steven Hawk, but you can call me Dr. Steve.” He ruffled his feathers slightly, raising the showy yellow crest that graced his bulbous head. “I’m a physicist and electrical engineer by profession, but I’m also trained as a physician. I’m especially interested in neuroelectrical studies, and I’ll be overseeing your treatment.”

Dr. Steve didn’t answer my last question. Apparently, it was none of my concern how he had learned about my background, nor was I going to be given an inkling as to why he had bothered.

* * *

Designed by the best avian minds, meaning the best minds anywhere, the therapeutic chamber, on the east side of L1, could be entered only through a lock with shiny copper doors. The large chamber was spotless, odorless, and bare and contained a wall of metal cabinets, a couple of carts bearing some unfamiliar and complicated-looking equipment, a few steel step-perches for visiting birds, and several other pieces of utilitarian enameled gray metal furniture.

There was also a tall, thinly padded steel gurney that I would rest on during the day for therapeutic reasons (every evening a more comfortable bed would be rolled into the chamber, so I could sleep more comfortably). With its burnished steel floor and its glass ceiling, the room looked aseptic; I supposed its uncluttered sterility was one of the reasons why it was so healthful.

* * *

To be continued...

Copyright © 2011 by Faith H. Goble