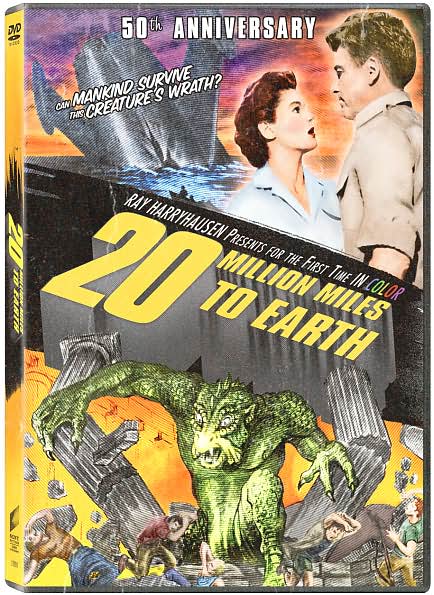

Nathan Juran, dir., 20 Million Miles to Earth

Creature Feature

reviewed by Steven Utley

Studio: Columbia

Story: Charlotte Knight et al.

Length: 82 minutes

Released: June 1957

And consider this opening sequence: Mediterranean fishermen are hauling in their day’s catch when a great 1950s wetdream of a rocketship (winged, pointy-nosed, etc.) suddenly shrieks down out of the overcast and ploughs into the sea. Most of the fishermen promptly make for shore, but two, with a young boy in tow, bravely enter the wreck through a rift in its hull and stumble about in a claustrophobe’s nightmare of semi-gloom, tangles of smashed equipment, and scalding clouds of steam. They find a dead astronaut, his face swollen with an ugly leprous growth. They find two other injured men whom they get out, into the fishing boat, and away, before the craft from the sky plunges to the bottom of the sea.

Yow.

After the rescued astronauts have been hospitalized, the same boy, playing cowboy on the beach, finds a cylinder containing a glistening gelatinous mass the size and shape of a large cucumber. He sells this flotsam to the medical-student heroine’s father, a zoologist who has been camping in the area. Unable to identify the thing, the zoologist at last gives up for the night, turns off the light, retires. Sometime later, his daughter comes in. Unnoticed on the table, the gelatinous mass trembles, bulges, is sliced open from within by a delicate birdlike claw. Something weakly emerges from the rupture, lies panting on the tabletop for a moment, then rises upon its hindlegs and begins cleaning particles of gunk from its scaly hide. Only seconds have elapsed since the medical student entered the room; we are perhaps a third of the way into the film’s running time, 82 minutes; what comes now is a scene loaded with tragic implications — the movie’s sublime moment. Joan Taylor, who still hasn’t noticed the newborn creature on the table, removes her jacket and turns on the light. The creature recoils, paws its eyes, and scares the bejeezus out of Taylor as it utters its first heartrending sound: a newborn’s cry of confusion and terror.

What follows is approximately par for the Giant Monster Gets Loose In Big City course. The big city in this case is the Eternal City, and there is a fight with an elephant at the Rome Zoo, and skirmishes with the Army, and a last stand at the Coliseum. Along the way, we learn that the creature has come from Venus aboard the lost spacecraft and that it has an appetite unusual in movie monsters: it subsists not upon the flesh and/or blood of teenagers rash enough to be necking in the woods late at night when they know there’s a fiend on the prowl, but upon sulphur.

Whenever I watch 20 Million Miles to Earth, which is pretty much whenever I get the chance, I have trouble deciding who is more afraid of whom. Unlike King Kong, who trashes New York City in his frenzy of desire for Fay Wray — unlike Godzilla, who razes Tokyo out of sheer reptilian cussedness — unlike, even, the nameless sea-beast that invades London to find her baby Gorgo — the creature from Venus gives every sign of wanting to avoid the hostile beings who persist in caging it, shooting it, sticking it with pitchforks, searing it with flamethrowers, electrocuting it. Even grown huge in Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere, it flees at their approach, tries to hide from them, lashes out only when avenues of escape are blocked. From first to last, it is patently a lost child far from home.

Copyright © 2007 by Steven Utley