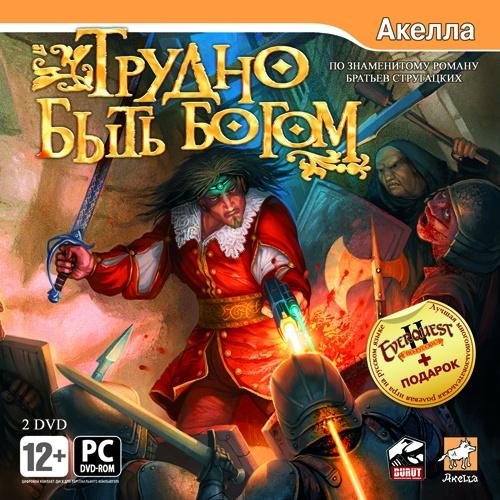

Arkady & Boris Strugatsky, It’s Hard To Be a God

reviewed by Bill Bowler

It’s Hard To Be a God Publisher: self, 1964 |

I’ve been rereading the Strugatsky Brothers, prompted perhaps by the recent death of Boris Strugatsky. It’s been ten years or so since I last immersed myself in their work. I’ve gone back to the beginning and am rereading them more or less in chronological order.

Last night, I finished It’s Hard To Be a God. It was striking and something of a jolt. Gone are the innocence, hope and optimism of the early works, of “The Land of Crimson Clouds” and “Noon: Twenty-Second Century.” Despair, brutality, violence, and injustice have intruded into the once bright and hope-filled world of the Strugatskys.

It’s Hard To Be a God is set in the 22nd century, in the age of space travel, when human civilization on Earth has progressed to a stage of advanced enlightenment. Humanity has entered a Golden Age. War, famine, and crime have been abolished.

Scientists and historians on Earth have formed a scientific body whose purpose is to search the Universe for alien life. Their mission is to observe and record, and to help newly discovered populations advance towards the enlightenment achieved and enjoyed by these future Earthmen. On a newly discovered planet, these future Earth scientists come upon the Kingdom of Arkanar.

Several of the researchers, including our hero, Anton, are dispatched incognito to the surface of the planet for close observation. They adopt the clothes, language and habits of Arkanar, and mingle with the populace, but remain wired so that sound and images are transmitted back to the orbiting observation spaceship.

|

The scientists discover that Arkanar is organized as a feudal society. A king presides over the classes of nobility, clergy, military and peasants. The king is well intentioned, but dim witted and easily manipulated. Under his rule, art and science are beginning to flower. A primitive printing press had been invented. The use of lenses to make distant object seem close has been discovered. Some beautiful works of literature have been written.

Don Reba, Minister of Court Security, schemes to undermine the king and to consolidate his own power. Reba frightens the king by staging mock assassination attempts and terrorizes the population with ax-wielding soldiers under command of his ministry. Reba launches an inquisition and commences the vicious persecution of intellectuals. His storm troopers round up and exterminate anyone caught possessing a book, anyone overheard expressing an independent thought, anyone who fails to follow the official dogma, anyone who openly advocates the principles of science or medicine, or who creates a work of art that fails to glorify the regime.

Anton — Don Rumata Estorsky in his feigned Arkanar identity — and his colleagues attempt to rescue as many individual victims as they can and to transfer them to an area of the planet with a less fascistic regime. The Earthmen hope to keep alive at least the seeds of enlightenment, to vouchsafe Arkanar’s future and to prevent the kingdom from spiraling down into the abyss of absolute ignorance and darkness from which it might never re-emerge.

Faced with the violence and brutality of murder, torture, political intrigue, war, crime, ignorance and betrayal, Anton begins to lose his objectivity. His scientific colleagues urge him to stay calm and continue his research, but Anton is outraged by conditions in Arkanar. He becomes personally involved. He begins to hate the persecutor, Don Reba, and he falls in love with Kira, an innocent young woman from Arkanar.

It’s Hard To Be a God is essentially the eye-witness “history of the Arkanar massacre,” the title of the late Aleksey German’s unfinished film of the novel. The story almost ends badly. Anton is driven to the breaking point by grief and rage. But the very final scene back on Earth, a lyrical, poetic postscript, almost an afterthought, redeems the unremitting brutality of the body of the novel and offers at least a glimpse of hope.

The novel was written fifty years ago, in 1963, and first published in 1964. The late 1950s and early 1960s were the time of the time of “de-Stalinization” in the USSR, when many of the most repressive policies of Stalin were ameliorated. In culture and the arts, this era was known as “The Thaw.” In literature, the requirements of Socialist Realism were eased. Solzhenitsyn was being published, as were poets such as Voznesensky and Yevtushenko, with his famous “Babi Yar.”

For some reason, the thaw began to refreeze around 1963. Boris Strugatsky wonders in his commentary to the writing of the novel whether Khrushchev’s humiliation by Kennedy in the Cuban Missile Crisis might have generated some backlash in the arts. In any event, strident denunciations of insufficiently pro-Soviet works began to appear in the newspaper headlines. “Formalism,” “abstractionism” and “pessimism” were again condemned.

Arkady Strugatsky’s initial concept of It’s Hard To Be a God was a light-hearted science fiction swashbuckler in the spirit of Dumas, with a future Soviet observer embedded in an alien world of swordplay, damsels in distress, etc. However, the hardening of the authorities’ position began to be felt in the Soviet science fiction and fantasy literary community. At the science fiction/fantasy Writer’s Congress, official speakers lashed out at the pernicious elements in the field, i.e., formalists, pessimists, etc.

Arkady Strugatsky feared this signaled a return to the excesses of the Stalinist epoch, when non-conformist literary figures were summarily executed or banished, and he decided to speak out. Boris Strugatsky shared his concern, and urged that the nascent swashbuckler they were co-writing be revamped along more serious lines. The swordplay, court intrigue, and damsels remained, but the themes and tone turned much darker, as the novel became a depiction of the violent persecution of intellectuals and artists.

The novel’s parallels, not only to the rise of fascism in Germany but to the rise of Stalin in the USSR, were obvious. It was rejected by the Strugatskys’ usual publisher, Detgiz (the State children’s publishing house), and by the serious literary journal Moskva. The authors tried to soften the text to make it more palatable to the Soviet authorities. On advice from the established science fiction novelist Efremov, for example, they changed Don Rebia’s anagram name and he became Don Reba. The manuscript remained unacceptable. In the end, the authors published themselves in a collection called Dalyokaya Raduga (Distant Rainbow).

Appearance of the novel provoked an unprecedented outpouring of denouncement of the Strugatskys in the official press. The critics, in the words of Boris Strugatsky, rolled out “the heavy artillery” for the first time. The novel has, nonetheless, remained in print in Russia since first publication and millions of copies have been published.

It has also been published abroad in a number of countries, including the U.S., translated to English from German, curiously enough. The U.S. edition was arranged by Forrest J. Ackerman, publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland, which magazine your essayist and perhaps others read avidly throughout the 1960’s. Theodore Sturgeon, who edited several volumes of the Strugatskys in English, called It’s Hard To Be a God “one of the most skillfully written, heavily freighted sf novels I have ever read.”

The question might arise as to whether the novel, with its “(anti?)-Soviet” thematics, has become dated. The story does reflect a certain historical period in the USSR, but it also transcends that period. Regrettably, suppression of free thought and glorification of State dogma are alive and well in the modern world and show little sign of abating.

Moreover, the novel derives much of its impact and staying power not from its themes, but from its deep characterization of the principals: Anton/Don Rumata; Kira; the scholar, Dr. Budax; the king; Baron Pampa, who befriends Don Rumata and chops up Inquisition monks and soldiers with his sword like so much sausage; and the sinister Don Reba, head of court security and eventual Bishop and ruler of Arkanar. It is the depiction of character, of personal relationships and conflicts, that gives the novel its emotional impact, its drama and pathos.

Books and Films

It’s Hard To Be a God is currently out of print in English. There seems to be one edition still with limited availability on Amazon for a rather exorbitant price.

On-line texts:

An English version can be found on line here.

The full Russian text can be accessed here.

There is a film version, a German-Russian production by Peter Fleischmann, available with subtitles on YouTube. The Strugatskys did not think highly of it, but it’s all we Strugatsky fans have got, so it will have to do.

If you want a more polished, Hollywood-style Strugatsky film experience, better to watch Inhabited Planet or Andrei Tarkovsky’s brilliant and quirky Stalker for which the Strugatskys wrote the screenplay, adapting their novella “Roadside Picnic.”

Copyright © 2013 by Bill Bowler