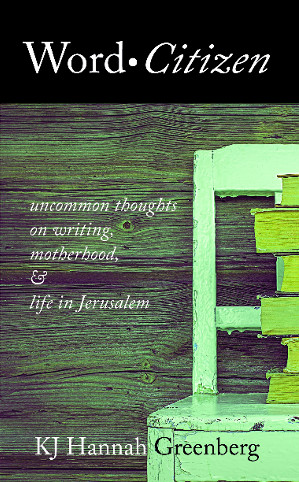

Channie Greenberg, Word Citizen

Thoughts on Motherhood, Writing, and Life in Jerusalem

excerpt

Word Citizen Publisher: Tailwinds Press (Sept. 15, 2015) ISBN: 0990454681 978-0990454687 |

Pulp: Literature’s Costume Jewelry

We groove fallalery. Our society gets down with junk, with fakes, and with inexpensive simulations. Thereafter, we party on in order to embrace babble and baubles or to otherwise have a good time with “low-priced” creative expression. That is to say, persons of our ilk attribute meaning to the availability of decorative trinkets. In the realm of literature, more exactingly, we actual and would-be movers and shakers place value on genred materials; we hunger after pulp fiction.

It’s not that the greater portion of educated people fails to be aware of the worth of fine writing. Most college graduates remain capable of recognizing keepsakes. Rather, it’s the case that well-informed men and women don’t want to expend resources on rigorous texts. More often than not, we sophisticated addressees cry for bookish balderdash rather than for erudite zinging.

In particular, as individuals fatigued from using our competence in differentiating among intentions, decisions, and actions, professionally and personally, few of us care that the literature, which we deem tastiest, is riddled with masked intentions, misrepresents social fidelity, and is devoid, overall, of pointers toward personal answerability. It’s not for nothing that genre fiction keeps growing in popularity.

Since we perceive ourselves as tired, and since we insist on comfortable, functional, and easy to peruse stories, it falls out that we want access to mysteries, westerns, science fiction, and romances. We hanker after narratives whose epistemically bald axioms don’t threaten the soft, squishy parts of our brains.

We demote the preciousness of critical and creative thinking in favor of holding close to cheap, lurid, and exploitative thrills. We run to hire plot devices and character types that allow us to assume that the social echelons above us are bereft of sensibility and that the social echelons below us have no clue about truth.

Crime stories, action-adventures, fantasies, and horror rock our communal socks as we welcome works that stroke our collective ego. Per the preponderance of our critical appraisals, literary fiction can jump the shark.

Predictable narrative structure, like the best of paste diamonds, suits us since we have long since dismissed the utility of unending cerebral exercise. In place of reflective reasoning, we demand quick, exhilarating circuits, and then, as true enthusiasts, get back in line for more. Informed nonsense liberates us, at least temporarily, form workaday concerns.

Such writing provided us, the folks who have to deal with grocery stores, paperboys, and carpet cleaners, with inexpensive escapes. We members of the middle class, who are bent on bourgeoisie ranking, vote for havens of predictable pejoratives about society’s watchdogs rather than for attacks on them. Grave or earnest training aside, we protect our need to skip out on morally commendable texts by buying corrupt ones.

That defense, the one which finds us devoting our dollars, euros, and yen to formulaic fiction, brings writers to the trough. Imaginative folks are not always so honorable as to be willing to sacrifice rent money in order to illuminate human nature. On a regular basis, artists of all sorts live lives of poverty, i.e. subsist in a manner that sharply contrasts with the ambitions fed to them by their mentors.

It’s hardly uncanny that, similar to the rise in importance of visual fluff and nonsense, as exemplified by the interest in and cost of art deco, pulp fiction, both vintage and contemporary, makes writers if not affluent, then at least financially fluid. Pandering to readers who want to distance themselves from principled rants and weighty themes is as easy as is scripting predictable resolutions and two-dimensional players.

There are additional advantages to be gleaned by writers who construct synthetics capable of: transporting unicorns or dragons, summoning moments of unrequited love, or displaying the demise of entire coteries of sharp-shooters. Not only do authors, from time to time, seek breaks from their analytical efforts, but they also have fun engaging in verbal dress-up.

There are few greater seductions equal to well-paid opportunities to roll around in the hay with otherworldly helpers, bespoken gals and gallants, and cretins of a criminal mindset. As a result, most writers succumb, at least now and then, to the temptation provided by genred lore.

Whereas matchmaking words like “twaddle” and “xylophone” might not suffice for very special work jocks, for most authors, puttering around with caustic fabrications provides enough release for them to return to facing down real life social problems, constraining publication specifications, rabid remarks from insensible critics, and shrinking openings for career advancement.

What’s more, writing about celestial fish, about female leads with loosened girdles, and about mysteriously sopping corpses does not have to lock writers into the realm of hack. Creatives can master literary fiction concurrent with taking up genred work without even having to resort to pseudonyms. Understandably, writers run as fast as they can to produce the textual equivalent of cheese puffs.

Contrariwise, shaping cosmetic discourse, while lucrative or liberating, continues to be an agonizing ordeal. Because such texts contain questionable concepts, such as heroes who always sacrifice themselves for their heroines, such as aliens that remain, forever, misunderstood, and such as cowhands that necessarily have to ride off into the sunset, they create for readers and writer, alike, problematic or, minimally, awkward exigencies.

Mechanical standards for plot, theme, and tone compromise not only readers’ laugh lines, but also the amount of stomach acid, jaw clenching, and phantom itchiness experienced by writers. Prose that reinforces habits such as rationalizing, minimalizing, and denying defective behavior, forfeits both readers’ and writers’ better qualities. Mentations that fail to reference sacrosanct verities or that fail to cause us to confront uncomfortably truths cost us. We enslave ourselves to some degree when we couple with narratives that sally forth toward happy-go-lucky, feckless, or other negligible outcomes.

Naysayers, it follows, stand morally correct in assessing: that beneath pulp’s surface sits a dearth of social consciousness, that it’s unbecoming for proletariats to mock the misfortunes of fictitious characters of similar social status, and that authors pay dearly, even at a “merely” corporeal level, for the genred pieces they pen. There can no more be an actual fountain of youth than there can be any authenticity derived from a prescribed list of literary elements. The creation of genred fiction calls for an outlay of writers’ guts. Viscera ain’t cheap.

In addition, opuses of costumed writing ordinarily contain words that fail to support, or that otherwise render improbable their content’s minutia. It’s unlikely that “his hand slid like a dove seeking perch,” that “its second head imploded on contact with the human’s grenade,” or that “Old Faithful broke into a trot at the same instance that the grand, golden orb dipped toward the horizon.” If a writer isn’t retching from compromised ethics, he or she surely is pained by society’s expectations for genred fiction’s verbal patterning.

Furthermore, authors whom consciously write pulp must remake their aspirations. It’s a stretch for certain writers to insert imaginary critters alongside of real ones, to fashion preposterous eventualities, to come up with fundamentally confusing interactions, or to variously evoke weirdness in their work, in particular when they have stopped taking for granted creature comforts because they have been training in or have been perfecting their craft. Such creatives approach assemblages of language with reverence. For those writers, the ones with steadfast integrity, it’s illogical to spend even a breath on intergalactic bazaars, September/May romances, or the actualization of third world despot’s plans to overtake advanced governments. The strain of constructing such work, even when it pays for pizza or for the monthly cost of a fourth-floor walkup, demands too much of those first-rate writers’ souls.

Interestingly, not only do some people see pulp as a balm and not only do others see pulp as a poison, but a third group of folks exists that considers genred literature as no more and no less than knick-knacks or curios. This last group of readers and writers regard genred fiction as adiaphorous in nature. Thumbing their noses at the more commonly adopted either/or dichotomy of ideals, this third group of thinkers insists on a both/and approach to cultural artifacts. For them, pulp both adds a splash to mental wardrobes which might not, under different circumstances, enjoy such color and hangs back as a despicable substitute for more substantive art (despite pulp’s related marketing perks, pulp’s facility with undulating belief, and its prestidigitation prowess, i.e. ability to reveal select moral certainties while concealing others). These people have no trouble holding both positions at the same time and as such, correspondingly fuel the pulp fiction market.

No matter. Apart from whether writers and their audiences champion, oppose or simultaneous champion and oppose the existence of genred writing, such literature seems destined to stick around. In the same way that the early Twentieth Century was a golden era for costume jewelry and for costumed writing, the early Twenty-First, Century, too, ascribes significance to such glittery goods.

About the Book

Most writers actually plod along. Whereas articles featuring a vista into an author’s ways and means tend to be glamorous (in order to benefit the publications presenting the texts), and whereas tweets tend to generously endorse their subjects, the greater portion of storytellers’ hours, even among the most highly successful writers, necessarily are spent pushing on an electronic or at a traditional implement. It’s small consolation to creative sorts that their work can often be performed in the comfort of fuzzy bunny slippers.

Word Citizen reveals that for writers, success can be sudden, sharp, or decidedly elusive. Talent is not always the engine that pulls audience share. Besides, timing and connections frequently amount to naught. Accordingly, writers must make efforts with their pens or keyboards, must expect nothing to go according to their plans, and when and if they reach some height of accomplishment, must expect that maintaining their readers’ attention is nearly impossible. For those reasons, most scribblers also work as engineers, busboys, English teachers, cab drivers, financial analysts, couriers, chemists, track couches, or as anything else that provides remuneration. Writing, in the best of times, is a glorified avocation.

This book’s fifty neat essays explore the nexus of the maternal and the writing professional. Its voice is the plaint of a midlife mom urged by peers to divest from family matters simultaneous with being pressed by her offspring and spouse to stay focused on their home. Using the rubrics “Working as a Writer,” “Growing as a Writer,” and “Parenting as a Writer,” Word Citizen shows how imperfectly, but successfully matters of the heart and of the head can get blended and how often adults ought to visit their local zoos.

Concerning Integrating Personal and Professional Roles

My adorable sons and daughters, as well as my beloved spouse, roll their eyes, if that, whenever I announce another of my manuscripts has been accepted. In balance, those same folks rant loudly, with what they believe is impunity, if I even hint at, think about, or consider the chance of maybe putting forward a possible draft of a text in which goofiness occurs, or in which, in their united or divided esteem, the referents are otherwise embarrassing. They do not like, for example, my works concerning explicit descriptions of physiological changes concomitant to menopause or my references to my prickle of invisible hedgehogs. To wit, my most beloved audience scrutinizes and attempts to sanitize my writing long before it reaches the desk of any persons appearing on a masthead or in a publisher’s office.

In response, I answer their outbursts with a fury of my own. Word Citizen is my most recent, mindful take on the business of playing with words. This assemblage is as much about my process of growing in my awareness of the business of writing as it is about my being a parent who writes, a writer who parents, and an integrated, albeit conflicted, creative. Said simply, this book, for all of its alleged pedantic glory, at some level, functions to thumb itself at my family’s sensibilities. No one asked and no one will ever ask those boys and girls and that middle-aged man if they wanted or want to live with a writer. Some facets of life are givens.

Words remain a force with which to be reckoned. Moms and wives who live as rhetoric professors, as journalists, as frequent flyer poets, and as storytellers tend to muck around with such power. Despite the turbulence associated with that sort of ride, the attendant views are well worth it. — KJ Hannah Greenberg

Copyright © 2015 by Channie Greenberg