The Strugatsky Brothers

by Bill Bowler

On November 19, 2012, Russian science fiction lost one of its greatest writers when the younger of the Strugatsky brothers, Boris Natanovich, passed away.

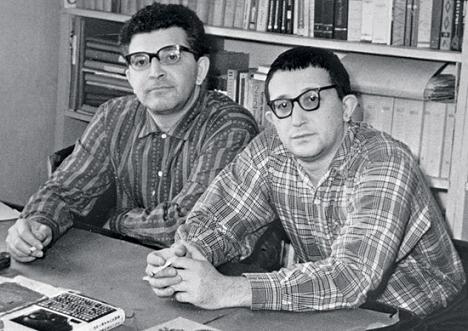

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky |

Boris, with his brother Arkady, co-authored a corpus of science fiction novels and stories. Writing under the Soviet regime, the Strugatskys were published by Detgiz, the Soviet publishing house for children’s literature, where a talented and courageous editor recognized the quality of the writing and fought to have it appear in print. The Strugatskys’ work appeals to readers of all ages. It’s simple enough for young readers and is at the same time highly sophisticated and thought-provoking.

The Strugatskys wrote together from the late 1950s until the late 1980s, when elder brother Arkady passed away. Between them, they completed some 25 novels and novellas, and numerous short stories. Their method of collaboration was simple and selfless. They passed the typed manuscript back and forth and wrote the text together. The resultant body of work is a chronicle of Russian life, philosophy, morality, heroism, and humanism in their peculiarly Soviet iteration.

Thanks in large part to Theodore Sturgeon, who discovered the Strugatsky brothers in the 1960s and organized their publication in the U.S., many of their novels are available in excellent English translations accompanied by Sturgeon’s commentary.

Science fiction and fantastika are serious business in Russia and Central Europe. Great authors like Karel Capek and Stanislaw Lem worked in the genre. In Russian, the tradition begins probably with folk tales like “Baba Yaga” and “The Invisible City of Kitezh.”

Many of the major Russian writers worked in the fantastic mode. To name just a few:

Gogol’s “The Enchanted Place,” “The Lost Letter,” “Vii,” and others

Dostoevsky’s “The Double” and “Dream of a Ridiculous Man”

Zamyatin’s “We,” the precursor of Orwell’s “1984”

Bulgakov’s “Master and Margarita” and “Heart of a Dog”

The Strugatsky brothers’ body of work represents a culmination of this tradition and forms the foundation for all that follows: Bulychev, Lukyanenko, Loginov, Divov, and many more.

The Strugatsky brothers were tempered in the fire of WWII. As young children, they were trapped in Leningrad, surrounded and under siege by the Wehrmacht. The population of the city was freezing, starving, sick and dying.

The two children were evacuated separately, first Arkady and his father, later Boris and his mother. They rode packed in the unheated backs of trucks in convoys across “the road of life,” the makeshift road laid across the one escape route through the cordon that the Germans had failed to consider: the frozen surface of Lake Ladoga. The truck carrying Arkady and his father fell through a hole in the ice left by a German bomb. Arkady was the lone survivor. Boris and their mother followed soon after and made it across.

Both brothers became scholars. Arkady studied English and Japanese and translated both languages into Russian; Boris studied astronomy. But writing and fiction were their first loves. The brothers tried their hand at writing, met success, and devoted the rest of their lives to it.

The protagonist of their first novel, The Land of Crimson Clouds (1959), is a tough, Communist salt-of-the-earth tank driver named Bykov (“Bull”), a heroic character straight out of the Great Fatherland War. But as time passed and their thinking evolved, the Strugatskys began to depict a more somber and ambiguous world populated with new types of characters, ultimately, ones like the disheveled outcast “Red” Shukhart, the Stalker.

At the time the Strugatsky brothers were writing, the Soviet government enforced the tenets of Socialist Realism. All artists, all writers, were required to depict Soviet reality in a positive and uplifting light, with morally upright characters and a bright future. Pessimism regarding the Soviet Communist future was considered pernicious and not permitted. The worlds the Strugatskys depicted were complex, paradoxical, full of hope but also despair, suffering, cruelty, injustice, and moral ambiguity. Although their work was set in the distant future and in various locations of outer space, the censors cleverly detected a thinly disguised critique of Soviet reality and found it necessary to suppress the work.

As a result, the Strugatskys’ writings circulated underground and were widely read. They have entered the canon of Russian literature, and are known and loved today by virtually every literate Russian. Their novels have been made into films by internationally renowned Russian directors such as Andrei Tarkovsky and Fedor Bondarchuk .

Arkady and Boris Strugatsky |

Characters and themes reappear throughout the novels. Leonid Gorbovsky and Maxim Kammerer are “progressors,” future scientists who devote themselves to making contact with alien species and “progressing” them, i.e., helping them to advance and become enlightened. In their space travels through Universe, the Earth scientists find traces of a more ancient alien civilization, “the Wanderers,” a mysterious race of aliens who, the evidence suggests, are “progressing” mankind.

The Strugatsky’s titles are clever:

“Noon, 22nd Century”

“”Monday Begins on Saturday”

“A Snail on a Slope”

“A Beetle in the Ant Hill”

The characters are endearing, believable, lifelike, and utterly human in their strengths and foibles. The settings are vivid and detailed. The plots are intriguing, and the thematics are heavy, “fully freighted” as Sturgeon put it, full of philosophy and morality, as they must be in any good Russian novel.

In “The Doomed City,” everyone changes jobs periodically. The man driving the garbage truck in chapter 1 is a powerful government minister in chapter 3. The results are not promising.

In “It’s Hard to be a God,” the scientist-progressors discover a planet that has reached the unfortunate stage of development roughly of the Spanish Inquisition. All efforts to intercede for the sake of good prove misguided and backfire horribly, bringing to mind Mephistopheles’ words to Faust, “I am that force that desires good but accomplishes evil.”

In “Inhabited Island,” an Earth spaceman crash-lands on a planet where the government has built a network of towers that beam mind-control rays to subjugate the population.

In “Roadside Picnic,” Stalkers illegally break into the “Zone,” a place where an alien spaceship has apparently touched down. The government has cordoned off the area, but freelance black-market Stalkers loot the Zone of priceless and very dangerous alien artifacts. Asked why the aliens would have stopped on Earth and left such mysterious objects in the Zone, the scientist Dr. Pilman speculates that we humans in the Zone are like ants swarming the site of a roadside picnic after the picnickers have departed, leaving their trash strewn about.

With the death of Arkady, the brothers’ literary output ceased. Boris, however, continued to write commentaries to their work and to play a prominent role in Russian literary life and culture. With Boris’s death, the curtain has finally come down on one of the most successful collaborations in world literature. We are very fortunate to have the Strugatskys’ legacy.

Copyright © 2012 by Bill Bowler