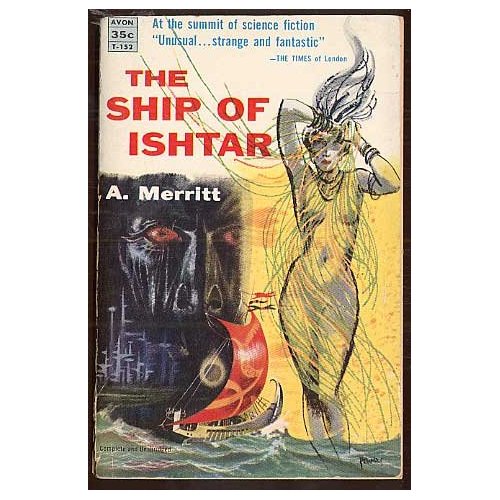

A. A. Merritt, The Ship of Ishtar

reviewed by Danielle L. Parker

The Ship of Ishtar Publisher: Avon, 1926 Length: 331 pp. ISBN: 2744176516 978-2744176517 Available at Amazon and Project Gutenberg |

Some of these books date nearly to the Victorian era. I’ve tried in each case to decide whether the stories still offer anything to tempt a modern reader (Edward Bulwer-Lytton, you are a creature of your time, I’m afraid). Up until now, I’ve been surprised at how readable most of these works remain. Perhaps classics remain classics. But now we come to seminal fantasy: The Ship of Ishtar.

A modern-day (er, for Merritt) archaeologist, Kenton, examines a mysterious block that proves, when cracked, to contain a marvelously detailed toy ship of ancient Babylonian times. The ship and its toy figurines are magic symbols of a real ship and the doomed travelers that exist in an alien world.

Kenton is drawn into that world, and finds himself caught in a battle between the pearly pink worshippers of the goddess Ishtar and her arch-rival, the gloomy, sneering god of the underworld, Nergal.

On the ship, unfortunate humans, often possessed by their patrons, battle each other as proxies for their none-too-kindly gods. The god of wisdom, Nabu, tries to intervene in the spiteful rivalry, and even loans the hero Kenton his sword and his advice.

But in vain. Kenton’s not interested in being a protégé of the god of wisdom. And like giant red-faced children pounding their heels in temper tantrums, Ishtar and Nergal are determined to continue their scream-fest, to the annihilation of their mutual and sadly misled worshippers. All I can say is, no wonder we did away with gods. These two are four-year-olds writ large.

Merritt’s tale of spiteful gods hurling human play toys at each other is a great occult fantasy premise. The prose, peppered with exclamation marks and loaded so heavily with baroque ornamentation it sometimes topples, is still intermittently gripping. Certainly you’ll read nothing remotely like it in a modern novel. I teetered between fascination on one hand and thinly suppressed giggles on the other.

But in spite of those merits, the book failed for me. I couldn’t sympathize with the human victims in this potentially grand tragedy.

One of the fascinating aspects of modern-man-transposed-into-fantasy-world stories is that the modern reader stands in the shoes of the protagonist, seeing strange and alien sights with the same shock and awe.

Alas, Kenton, a man of reasonable intellect presumably in his own world, loses brain with every ripple of brawn he gains in his new magic world. Not for one instant is his viewpoint that of the modern man he supposedly is. He turns into instant barbarian, slicing heads, slinging priestesses over his shoulder, praising the spiteful silly Ishtar as if she really were the Goddess of Doves, kidnapping and chaining slaves, sinking ships all hands aboard without a qualm, and never once thinking What the heck am I doing here? Did I give up modern plumbing for this?

There’s no thrill of this-is-how-I’d-feel-if-I-were-there for the reader. Instead, we dive straight into the headset of a credulous pagan barbarian, and there we stay. If you cherish fantasies of such activities, drop in. Myself, I rather preferred Leiber’s Gray Mouser. There was no need to present Kenton as modern-man-goes-ape in this book in the first place. The man is ape from page one.

Read The Ship of Ishtar for its over-the-top baroque occult fantasy. Park your own intellect somewhere else when you do. Experience the work as it should be experienced: a mood piece. There’s nothing like it out there now (occult fantasy being a genre that could use some great modern practitioners). It is, in its own way, a splendid savage barbarian fantasy presented with no winks and no apologies. But by the time the toy figurines on Ishtar’s magic ship meet their ignominious ends, you may be thinking There, but for a brain, go I.

Copyright © 2012 by Danielle L. Parker