History of a Déjà Vuby Bertil Falk |

Part 1 appears in this issue. |

| conclusion |

VI

With all this, we have specified some phenomena of specific interest to us: bats, bat-wings and cloaks. And let us start it all over again from another point of view. The Spanish cloak had at the turn of the 19th century, through the 20th century until today gained a strong standing within escapist literature, light reading, cartoons and in the movies in the United States as well as in Europe.

When it comes to heroes in cloaks, figures like the principal characters of novels in keeping with The Count of Monte Christo and The Three Musketeers were popular. The French hero Fantomas was the protagonist of 32 novels by Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain during the 19th century and in 1913 Fantomas was the hero in a series of motion pictures.

Fantomas was a forerunner of the number one masked and cloaked hero of the 1930’s. The Shadow, in a slouch hat, was written by Houdini’s ghostwriter, Walter Gibson, who wrote his Shadow stories under the pen name Maxwell Grant. The Shadow was a most successful pulp magazine during the Depression. Nobody in the United States could avoid noticing this hero, who furthermore made a sensation on the air, where the elusive Shadow was “embodied” with ominous sublimity by a voice that belonged to a young Orson Welles and others.

In the summer of 1931 The Living Shadow was published. The Shadow’s cloak fluttered like a dark piece of cloth through the 1930’s and the 1940’s. Even though both the pulps and the radio shows are long since gone, he even now turns up here and there, now and then.

Furthermore, 1931 was the year when Hungarian-born Bela Lugosi put on his cloak in the Universal Studios in Hollywood for the first Dracula movie with sound. Lugosi was transformed into a bat when he fled his adversaries. Actually, when Lugosi died, the cloak he wore was buried with him together with some other Dracula paraphernalia. And, important in this context, with the Dracula movies the cloak and the batwings met.

In the comic strips and Sunday pages, cloaks and mantels streamed and fluttered from behind the heroes and villains alike. The Dragon Lady of Milton Caniff’s comic strip Terry and the Pirates had a cloak, and the elegant magician Mandrake by Lee Falk was dressed in a top hat, tail coat, and a red cloak.

In 1934 Bob Kane must have known The Shadow as well as Dracula. There have been many different things said as to how Bob Kane hit the jackpot. This is the version I first heard and since it fits into my déjà vu, I will go for it here.

Kane knew about at least one of the flying machines Leonardo da Vinci designed. At least, Kane has said — in one version — that he was influenced by Leonardo’s inventions at the age of 13. He did some preliminary, crude sketches of a bat-like or birdlike man. He used da Vinci's flying machine as the basis for influence and inspiration.

But before we return to Bob Kane and his bearing on my déjà vu experience we will once again begin the beginning of a new thread that also is a weft in our web and has to be observed to make the pattern a complete one.

VII

One of the supermen of the science fiction in those days was Doc Savage, who had his own pulp magazine. He was a bronze-colored man, strong and intelligent. In the advance publicity he was called a superman. In Cleveland, Ohio there were two teenagers, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. They were dreamers and science fiction fans. They also read stories about Doc Savage and other supermen.

In 1932 they created a stenciled fanzine they called “Science Fiction. The Advance Guard of Future Civilization.” In number three they published the story “The Reign of Superman,” written by Jerry Siegel. It was about a jobless man standing in line in a soup kitchen. He is given an elixir, which among other things makes it possible for him to read other people’s thoughts. Joe Shuster illustrated the story and by that made his first Superman-drawing without knowing what it would lead to.

But a seed was sown. One hot summer night in 1933, Jerry Siegel could not sleep. Hitler had seized power in Germany. His idea of an Aryan super-being — an evil Übermensch — pushed its way forward in Europe. Jerry Siegel dreamed about another kind of Superman. A kind being, who protected the weak and the frail, a strong man, who would have stepped in when Jerry and Joe were mobbed by the stronger kids in the playground, a kind of savior, a being from another world.

The idea grew. Over and over again that night, Jerry got up to write down his ideas. Superman would come from the planet Krypton. As a baby he was sent to Earth in a spaceship. He would keep his strength a secret and conceal it under a layer of timidity as the reporter Clark Kent. Jerry did not sleep at all that night. In the morning he rushed over to Joe Shuster. That evening Superman had been created on Joe’s drawing board.

When I met Joe Shuster in Queens on November 26, 1975, he said: “I conceived the character in my mind’s eye. It would have a very, very colorful costume of a cape and very, very colorful tights and boots and the letter S on his chest. That was my concept of Jerry’s character from what he described.

“He did inspire me because he said that this has gotta be a supersuper character that people would recognize and instantly identify with. Each child and each reader will identify with this character and he can do anything in the world and the main thing we had in mind — I guess we were both very idealistic at that time — was to have one hero, a superhero, who would stand for justice and for truth and honesty and to overcome the evils of the world.

“You know, it’s a concept that probably goes back in years and years in literary history, because of course there was Robin Hood and perhaps other famous literary characters, but our concept was to combine the best traits of all the heroes of history that have ever lived, that have ever existed.”

One of the four or five most revolutionizing mythological figures of the 20th century was born out of the likeable disposition of two poor working-class boys during the Depression. A kind of savior against a backdrop of Art Deco skyscrapers and unemployment lines. When he flew through the air a red cloak streamed behind him in a way it never before had fluttered either behind The Shadow, Mandrake, Zorro or anyone else.

For five years the two boys tried to sell their creation. At the end of the 1930’s National Periodicals (D.C.) decided to use Superman in their new publication, Action Comics. In June that year, No. 1 was published and Superman met with an enormous success. Unfortunately, the smart people of the publishing house had persuaded Jerry and Joe to waive the right to Superman. A sad story in itself, though it has no bearing on my déjà vu.

VIII

And young Bob Kane was still around somewhere. Kane’s drawing of Leonard’s flying sleigh with bat-wings and a masked man with bat-ears had been put aside for years in a box with baseball bats and odds and ends in the attic. At the end of the 1930’s he came to D.C., where he did some background drawings and he experienced the unprecedented success of Superman.

He wanted to do something similar and asked the editor of Detective Comics, Vincent Sullivan, if he could create a superhero. Sullivan was positive. Over the weekend Bob Kane in his home took a magazine with Superman and modeled the anatomical structure of Superman on a tracing paper. Then he was going to create a costume for his hero.

At that point Bob Kane remembered the bat-being he had drawn some years earlier when he was 13 and that was inspired by Leonardo da Vinci. Bob Kane hunted out the old box from the attic. Among balls, roller-skates and whatever, he found the sketches at the bottom of the box.

Bob Kane equipped the Superman body with a cloak that looked like bat wings. He supplied his hero with a mask in the shape of a hood with bat ears. And where Superman had an S on his chest, Bob Kane simply put a bat.

This is one version as to how Batman was born. And Batman has ever since May 1939 been seen jumping from one frame to another with his blue and black bat cloak fluttering behind him. And he often used it, as did Swedenborg’s schoolboy and da Vinci’s “tent-man,” as a parachute.

IX

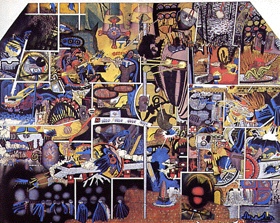

Batman’s cloak had caused the déjà vu. It was that cloak which met my eyes everywhere in Sitting. A Spanish cloak, so well known but at the same time totally liberated from its superhero body, released from its comic book context but still placed in a similar serial frame pattern that had been its natural environment ever since 1939. And not only the cloak liberated from the body, even the very color of the cloak liberated from the cloak, floating around in the artwork.

The déjà vu was explained.

To me there was even more to it. The Sitting of 1962 I faced in 1979, excellently demonstrated what Fahlström said in his concrete manifesto of 1953. There Fahlström advocated delivering the words — these building blocks or pieces of dough — from their heavy meanings and dissolving them into their constituent parts, regrouping them into new unexpected combinations.

His idea was understandable. Behind us were decades of surrealism and traditionalism. Fahlström himself had a surrealist period. In 1948, the traditionalist T. S. Eliot got the Nobel Prize. In his poetry, the whole weight of a word’s meaning during its history was supposed to do itself justice. What was more natural was that someone — Fahlström — went in the opposite direction and rid the words of their meanings, symbol values, private or universal, instead of meaning, sounds and rhythms; languages, sentences and words like a dough-mass, kneadable.

He wrote: “We can find undreamt-of value in the — from our present viewpoint — most truncated and disjointed word and sentence structures. MANIPULATE the material of language: that is what will justify a label as concrete. Manipulate not just overall structures: rather, begin with the smallest elements, letters, words.”

It all gushed forth like one single evolutionary, revolutionary form of poetry. The mumbling of simultaneous reading aloud, rhythmical word orders, homonyms, reversions. “The simplest course is to turn to the logic of primitive peoples, of children and of the mentally ill, which abolishes contradictions, the logic of simile, of sympathetic magic.” Fahlström tried to illustrate his method with the poem MOA (1).

There one could read expressions like “få july örom öratar,” “foiröra ap-moa rak” or “bröst apar in drar st ort,” based on the Swedish language and just about as intelligible to a Swede as anything from Finnegans Wake is to an English-speaking reader. But while Joyce in an Eliot-like way added to and doubled the meanings of the words he created and manipulated, Fahlström stripped the words of their meaning and used the sounds by picking them to pieces.

One should be aware that Fahlström by means of his manifesto did not preach per se that poets should avoid committing themselves to such things as social and political questions. He wanted only that they at least casually put aside tenor, standpoints, private concerns etc. as an experiment, in order to sharpen their means and their methods, The important thing was to give shape to new means of expression, which could be added to those already existing.

We should, as Fahlström put it, “take our leave of the systematic or unsystematic depiction of personal-psychological, contemporary-cultural or universal problems.” But after this stage, the poet (or the artist or the composer, Fahlström never limited his concrete principles to language) could return to the social problems and with an increased decisiveness attend to the artistic creativity without shutting her or his eyes to the real world.

Fahlström went on from the manifesto into an social activity permeated with all kinds of art forms, where the concrete was reduced to what it had been to begin with, i.e. technique and method and perhaps — I am not sure on this point — also a kind of sounding board.

The media reports — that Fahlström was cutting comic books in Greenwich Village — were now put into their natural place in context. He was there, cutting and cutting and among many other things like Krazy Kat he cut Batman’s bat-like Spanish cloak out of Bob Kane’s frames as they repeatedly appeared in Batman and Detective Comics.

The way he used this ancient garment now becomes an excellent illustration of the concrete technique he once had preached when it came to the handling of language in his manifesto. For in Sitting the method is exactly the same as in his “poem” MOA (1). The method has only been transferred from word play to visual art.

The cloak, with its atavistic and prehistoric roots, has been pulled out of its comic book context. Even the experienced comic book reader — like myself — suddenly becomes uncertain of the symbolic value of something well known to the eye. The cloak of Batman had been changed from being a heavily symbolic token to become a visual building block liberated from its old meanings.

X

Thus we have observed a déjà vu, a motif, a subject, a theme. A straight line runs from Leonardo da Vinci via Bob Kane to Öyvind Fahlström. This line of tradition may seem strange, but it is there. From frame to frame in Kane’s cartoon, a cloak streams from the shoulders of Batman. In Sitting the same cloak, now freed from its Batman, flutters in a completely different environment.

A comparison between a page of Bob Kane’s Batman and Fahlström's Sitting uncovers that the only thing they have in common is the primary form Fahlström deprived of its given aspects.

Fahlström not only applied his concrete theory in his artwork. He transcended his own objective and succeeded in transforming the comic book pattern without even changing its given, technical conditions. Its given meanings he simply cut away.

Postcript:

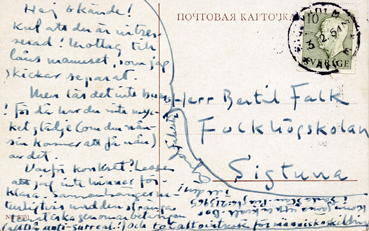

This is what he wrote: “Dear unknown! Nice that you are interested. Receive as a loan the manuscript, which I will send by separate mail. But don’t read it straight away. If you do, you won’t find delight (if you ever will) in it. Why concrete? Sorry, but I don’t have time to explain. It has of course to do with the rigorous thematic well worked-outing (in other words: anti-surreal !) and a total lack of interest for character portrayal. If you like, come up some evening. I live in the Old Town. Give a ring 213965. Till then Öyvind Fahlström.” I never called.

Comment:

The quotations from the English version of the manifesto “Hätila ragulpr på fåtskliaben” (Hopy bapy bthuthdth thuthda bthuthdy) is to be found in Öyvind Fahlström (The Salomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1982).

the World

The quotation of Joe Siegel is word for word from a recorded interview I did with him in Queens on November 26, 1975.

Copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk