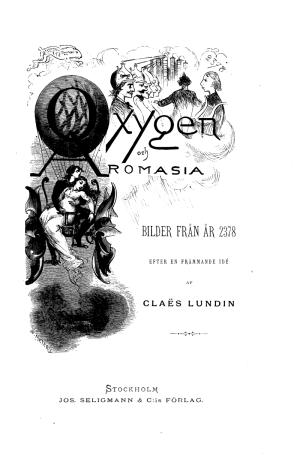

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 13 appeared in issue 267. |

| Chapter 14: Election Day |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

The voting machines were in full operation in all wards within the third district of Majorna. The voters did not have to appear in person at the polling stations. They sent their votes by telephone-telegraph, a procedure had been used for several hundred years.

The method had undergone constant changes and improvements until people even in the most distant parts of the district got their votes counted instantaneously by the voting machine. The machine immediately added them to the votes already cast and forwarded the sum to the central machine, whence the newspapers received information about the outcome of the election every five minutes and how many votes every one of the candidates had received.

The machines presiding over the election were run by one single engine-man inside every voting station, but at the central machine two engine-men were employed. Mistakes were out of the question, for the machines were carefully examined by the Government’s engine-men, who furnished them with a Government stamp asserting that they were well managed and correctly greased.

“How is the election going?” asked Mrs. Mild-Severesell, herself a representative with a great reputation.

“Look, here is our old Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal, her husband, Mr. Severesell replied. He was one of the chemists who had assisted the renowned Moleculeander in constructing the big albuminous factory at the former Gammelport and later had been one of the founders of the even bigger lard factory at the Haga block.

Mr. Severesell was a famous chemist, probably the first inventor who created albuminous elements out of the most elementary constituents, from which not only bread but even meat could be made as well as generally tasty nourishment. To be sure, this invention had not yet spread over all of Scandinavia, but the enterprise was already guaranteed, especially since bank director Giro had taken charge and succeeded in creating a magnificent joint-stock company.

“Our old Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal“, Severesell said, “states that Aromasia Doftman-Ozodes still has gotten the most votes.”

“But that cannot be possible,” his wife objected. “She was killed yesterday evening.”

“Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal has precise information from the central voting mechanism and the newspaper is seldom caught distributing an incorrect statement. Correct statements have been handed down for more than five hundred years.”

“I just read The Proud Air-Bubble,” Mrs. Mild-Severesell said, “and it urges the voters not to waste their votes on a dead candidate.”

“On the contrary, the Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal reminded voters a couple of hours ago that they still aren’t convinced of that Miss Ozodes is dead. Therefore one should not avoid voting for her. This reminder seems to have produced an effect.

“It is also a question of showing how groundless the statement is that was published in the Stockholm paper Next Week’s News last week. It stated that Miss Ozodes would not be elected this week. If it turns out that this paper has spread a rash piece of news, then it will get a bad reputation.“

“Oh, my friend!” his wife exclaimed. “Never before have I found that you have such a bad knowledge of human nature. If a newspaper in our time publishes a rash piece of news, it doesn’t at all damage its reputation. The news is the main thing. Rash or not, that’s totally unimportant to the public. Authenticity and truth are not needed any more.

“Incidentally, they have never been needed. Our Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal is too far behind the times, if it still puts authenticity and truth above all... Listen to what people shout outside our windows, and see how people behave. That’s the best proof of what I’m saying.”

A crowd of people had gathered outside the windows, partly in the air as bike-riders, partly on the balconies and on glass-tracks of the very street. People jostled one another around some newspaper distributors, who were flying to and fro, up and down outside the houses. They were lowered to the ground, touched the sidewalks and once again took off up to the upper apartments.

“Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal!” some distributors trumpeted forth through their trombones, the sound of which was brought about by the bike machinery without any special effort by the barker.

“The Proud Air-Bubble!” others screamed in a similar way.

“Next Week’s News!” it was boomed with even sharper trumpet blasts.

All were similarly eager, flapped similarly untiringly, treated the exclaiming-mechanics with the same skilfulness, for all were partners of some of these newspapers.

But not all had the same success. The sales differed widely. Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal did not seem to be in great demand.

“She’s too old,” it was said. “More than five hundred years! Such a newspaper can’t know anything new.”

“No one with a good head for business,” someone else said, “would wait until something is truthfully confirmed before printing it in the newspaper. What insufferable waste of time!”

“That paper makes a fool of itself!”

The Proud Aír-Bubble sold somewhat better, but most newspaper readers gathered around the sellers of Next Week’s News.

“Look, that’s a sheet that’s alert,” people said.

“It has something to tell us.”

“It’s running, no, it’s flying ahead of its time.”

“That’s the mission of a newspaper.”

“Give Next Week’s News to me!”

“I want Next Week’s News!”

“Well, let me have Next Week’s News!”

Everywhere it sounded like that. People fought over the newspaper and when they had snatched a copy, they devoured the content hook, line and sinker, with extra-bold headlines, body lines and 8-point paragraphs.

“Aromasia Doftman-Ozodes has not been elected in Gothenburg,” was printed with big, black letters.

“But it isn’t mentioned that she died horribly the day before the election?” someone remarked.

“Why should that be mentioned? The sheet doesn’t want to be tactless.”

“Oh, well, then one cannot of course vote for her.”

That was the end of those discussions.

The chemist and his wife had also bought Next Week’s News, actually two copies in order to prevent waste of time. The wife read her copy while she nursed her youngest child, her husband read his while he thought up a new combine of water, air and carbonated lime in a new attempt to make palatable meat and bread.

“Love is what made me a foodstuff chemist,” Seversell used to say, and when his friends asked him how come, he told them that he, who loved family life in his home, did not like to travel to the inn every day with his wife.

Nor did he want her, because of anxiety about the kitchen, to be distracted from her work at parliament, for which she had shown such inclination and capability. Therefore he exerted himself to discover the substances from which artificial food could be extracted, food that needed no further preparation for being consumed.

His efforts had been successful and would probably one day be of advantage and a blessing to the whole mankind, even though no one had as yet been known to benefit from them outside Gothenburg, which always was in the forefront of progress.

As early as 2378, people in the vicinity of that city began to think of using the fields for other purposes than corn production and above all to make themselves independent of the wheat cultivation in the rest of the country.

They had already begun shipping artificial substances of all kinds to England: not only artificial wheat bread, which had been invented in eastern Sweden some time before and had been sent abroad through Gothenburg. However, it was only as a replacement for the oats that had been sent to England in the past; but the cultivation of oats since long had been abandoned in Sweden.

“Thus it’s love that has brought about this revolution within the public economy,” someone remarked.

“Most certainly, and it’s the enterprising spirit of capitalists that has performed these works of charity full of blessings.”

But in the other parts of Scandinavia, people did not believe very much in the great inventions from Gothenburg. Farm engineers continued to cultivate the soil in order to create good harvests by means of the weather-factories. Tremendous herds of cattle still grazed the extensive meadows of Norrland.

“There will come a day when all this will have undergone a total change,” people said in Gothenburg, but in Stockholm people did not want to listen to such talk.

“The Gothenburgers think that they can re-create the whole world,” they said in Stockholm, shaking their heads.

“We’re practical,” the Gothenburgers said.

“And we even make practicality a joint-stock company,” said bank director Giro.

But on the election day, Mr. And Mrs. Severesell were reading Next Week’s News while they devoted themselves to the above-mentioned occupations at the same time. The man had declared his will to invent some means by which his wife could even be rescued from nursing their children, but she did not want to hear about anything of the kind.

“I take care of my children myself,” she declared with certainty. “Women of our time shall be able to show that the home will not, as people used to think, suffer from housewives’ having a profession or devoting themselves to public duties. If time is organized properly, a woman will manage to do both things. If she only has the necessary knowledge and a serious will, then she will be able to work in the public sector and in private life. Society ought to feel the need of both.”

In practice, she showed that her view was perfectly true. That was at least what 24th-century writers were saying.

“Hm, I don’t believe Next Week’s News,” the house-father said after reading the paper.

“Neither do I,” the housewife uttered.

It was rarely the case that these two, wife and husband, were of different opinions, and yet they were both quite independent with their own fully developed personalities.

“But other people are guided by the paper,” the wife added. “Now I’ll go to the standing committee of supply. I must avail myself of the opportunity, for it’s not unlikely that the great Government regulating machinery will have already begun its operations today.”

It was not long until the central voting machine had collected all the votes. Only a few of the people entitled to vote, that is those of all the men and women within the third district Majorna who had reached the age of 20, had not fulfilled their obligation.

Everyone who had omitted to fulfil the obligation to vote was immediately fined quite a big sum. In that respect, it was rigorous. Nobody was permitted to shirk her or his civic duty. And as we have seen, everything had been done in order to make the fulfilment easy.

Oxygen Warm-Blasius, the weather manufacturer, has been elected.

That could be read on the many telegraph-boards everywhere in the city, and the information was immediately spread all over Scandinavia, for in these days people were anxious to know the results of a parliamentary election.

The turnout was of course greatest in Gothenburg.

The outcome should certainly not have been a surprise. Even if Aromasia had been alive, she had nevertheless not done very much to get elected, so it was not surprising that she had gotten a small number of votes. People were not accustomed to such indifference or, to use a word obsolete in the annals of Parliament, modesty.

But after the horrible event the previous night at the Örgryte block, one could hardly believe that anyone would have wasted a vote for Ozodes. People were not accustomed to voting for dead persons, even though it did happen on occasion, that people cast votes for those who slept away their lives.

However, the attitude of Commercial- and Air Traffic Journal seemed to have saved many votes for the candidate the district itself had invited, whether she were alive or not.

“That is more than strange,” it was said in the city. “They vote for a deceased person and listen to a newspaper that seems to be stricken in years.”

“Believe me,” an old politician objected. “That newspaper, though fairly advanced in years, will retain its influence for a long time after all the young newspapers have gone to rest for good.”

“Nothing has convinced us that Miss Ozodes is dead,” Giro said, “and therefore nobody should have failed to vote for her.”

“He probably made a joint-stock company of the election,” someone whispered.

However, Oxygen was elected, and the joy among his supporters turned out to be lively. Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar flitted from house to house singing victory songs, though some people said that it sounded like the croaking noise of a raven.

Miss Rosebud did not appear to be as happy as one would have expected. She looked for Apollonides without finding him. She even seemed to be inconsolable because of the death of Aromasia.

“Who could have thought of something like this?” she incessantly repeated.

But the public did not know anything about the anxiety of Miss Rosebud. They only talked about the election of Oxygen.

“It’s a credit to Gothenburg,” it was said, “to be represented in the parliament by such a famous weather manufacturer.”

“He’ll often have us sailing with a fair wind.”

“With him among us, we’ll know how the wind is blowing.”

“But it’s a pity that the beautiful Aromasia would end her days in such a tragic way. She was certainly beautiful.”

“Extremely beautiful!”

“And she was a skillful financial manager. She could have been very useful.”

“But now air-art has probably come to an end. Who would dare go to an air-concert from now on?”

“The brain-organ cannot cause such an accident.”

“Have you heard that they’re shipping out pit coal from China?”

“Rubbish! Where would China get pit coal?”

“It’s artificial of course. It’s said to be someone employed by the trading house Tsi-ho-ka-ka-lo in Beijing, who has exactly copied our Halland coal.”

“What a cunning devil! I would like to get in touch with him.”

“What if we made a joint-stock company?”

That how they talked in the Crystal Palace at the big Otterhällen. Most people seemed to be satisfied with the election result while at least many of them regretted the horrible end of Aromasia. But then they returned to their office jobs, and in the evening they made excursions to Trollhättan and the Pater Noster skerries as well as to the underground carriages down to the Gardens of Okeanos, where a big party was once again under way.

The first 500 meters of the new Scandinavia-Scotland tunnel was opened. It had been completed, absurdly, in no time at all.

“The whole work will be completed in a few months,” Giro said, “but we’ll begin the European-American tunnel before that.”

“And then we go on expeditions to the center of the earth,” someone added.

“Of course,” Giro confirmed. “I’ve already launched a joint-stock company for the big center of the earth line. A few stocks are still available.”

The stocks were bought up avidly.

The accident at the Öregryte block seemed to be forgotten. Nobody talked about Aromasia any more. But where had Oxygen gone? Nobody had seen him since election day.

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk