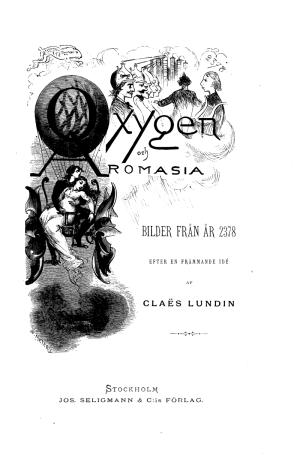

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 3 Chapter 4 appeared in issue 258. |

| Chapter 5: The Concert |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

It was late in the evening. An ancient person would have thought that the air was filled with swarming fireflies, but the shining points only constituted the radiation from the air-vehicles and were the equivalent of the coach lamps of the past.

It was late in the evening. An ancient person would have thought that the air was filled with swarming fireflies, but the shining points only constituted the radiation from the air-vehicles and were the equivalent of the coach lamps of the past.

These emanations were brought about through the discovery of a new natural force some years before the beginning of this tale, and industry immediately began to make use of this source of energy. It was used for street lighting, among other things, but in particular it was used to illuminate the vehicles that moved above the buildings and the public roads of the town.

The electric light that was used to illuminate cities at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century was to the newer lighting method as one of the prehistoric so-called tallow candles had been to the electric light. Later, many different luminescent materials of constantly increasing brightness appeared. Then this newest discovery was introduced. Its light surpassed that of all other artificial lights. But this light would also eventually find its vanquisher and successor.

The fireflies swarmed in thick flocks and in many layers. Then they spread in all directions, gathered again and once more spread here and there in the air above the big city. People were taking some fresh air after a day’s work, went to pay visits, to the playhouses, to the 31 public readings, to pleasures of all kinds.

A large number of people steered to one of the city’s concert halls, situated on one of the boulevards, just about were the street Tjärhofsgatan once had run.

It was a moderately small building, hardly bigger than the former Royal Palace. It was round and covered with glass or the kind of porcelain that had replaced the glass and was much more transparent than glass. Above the roof floated an enormous sun of the new luminescent material. Its clear shine penetrated the big concert hall and illuminated it as if it were daytime but without damaging the eyes.

When the music still exercised its control over the people, they had built one concert hall after the other in Stockholm, bigger and bigger. Wagnerian music steadily increased its claim on large spaces. That went on until all of the old Ladugårdsgärde was found to be insufficient.

But when that area became more and more built-up, and when people’s eardrums had long since been split, they pulled down the big concert halls or used them for other purposes. When the air-piano was perfected, such big concert halls were no longer needed. Buildings of a smaller size had to suffice. Only some of them were as big as the old palace, and they were much simpler than the music houses of the past.

In the old music halls, one had been forced to find room not only for dining halls and cafés but also for entire guesthouses. Symphonies had often taken many days to perform, and during the intermissions the audience took a badly needed rest in the guestrooms, but not until they fortified themselves with a potent meal.

In these guesthouses there also were clincs where skillful physicians treated listeners who were suffering from incessant yawning. In some of the music halls, there were even burial-places for those who had been musicked to death by trumpet blasts and the huge steam-organ.

Such things were not necessary in the concert halls or odoratories, where the scent concerts were performed. Only refreshment rooms and bathing cabinets were offered, and the concert hall took up the greater part of the building. It was still called a concert house out of habit, and the place usually had room for only ten thousand people.

The hall where Aromasia used to play her concerts was not even that big. Though she had herself invented machinery that subdued and distributed the fragrances in such a way that they seemed to be the same all over the room, she nevertheless did not want to play for more than seven or eight thousand connoisseurs at the same time.

Many people found that a little bit too restricted, but the artist based her opinion on her own, most complete calculations, and she probably had experiences that not everybody could perceive. The beautiful Aromasia was powerful at calculation.

The concert visitors began to arrive. Through a rather simple mechanism in the lobby they were relieved of their outdoor clothes. These clothes were made of material so thin and soft that they were easily rolled up, given a number, and pushed by the machinery into the many small boxes that moved and disappeared on their own back into the walls.

The same machinery also supplied concertgoer with the corresponding number, which also showed him to his seat. After the end of the concert the visitors could easily locate the boxes in which their outdoor clothes had been stored. A simple pressure on the metal button with the right number and the box came out of its hiding place. Vehicles were delivered and reclaimed in a similar way.

“Tonight, Miss Doftman-Ozodes entertains us with an altogether new composition,” Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar said to her neighbor Miss Rosebud.

“Is it a diplomatic-political creation or are we going to perceive something that describes the latest inventions within mechanics?” the pretty little miss asked, while she langorously stretched herself out in her comfy reclining chair.

All seats in the hall were couches of that kind. They were comfortable and had the same price tag. Tickets cost only three hundred francs each, and they were all booked.

“No, our dear Ozodes is said to have been persuaded into giving us a performance about nature poetry, as it was called in the past.”

“How ridiculous!”

“Indeed, but also quite interesting, I suppose. Let’s hope that we’ll experience something nerve-tickling. I feel a strong need for that. Besides, it could be quite instructive to be reminded of the antiquity, if only for the purpose of perceiving the superiority of our time.”

“Oh, look. There’s Saksander, the director and manager. He’s the one who is the head of the new Women-Tailoring, Ltd., a very decent man and very refined.”

A young man, somewhere between thirty and sixty, dressed according to the latest fashion, namely in embroidered sackcloth, approached the two women.

“Good evening, Mr. Director!”! Miss Rosebud exclaimed and offered the young man both her hands.

He nodded kindly and handed the ladies a pair of rose-colored and sweet-smelling cards. “This is the playbill for the evening. It was just printed out by the distribution mechanism,” Mr. Saksander said.

“The Seasons!” Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar exclaimed. “That’s exactly what I’ve heard about the new composition.”

“How ridiculous!” Miss Rosebud said once more.

The young lady was of an old family of the kind that in the past was called noble, but she was nevertheless a child of her time and preferred smelling something of mechanics rather than of politics.

“There is a scent of spring flowers,” Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar said and brought the little card to her nose.

At occasions like this, the programs had a scent that gave a feeling of the content of the concert.

“It’s said that Ozodes has been persuaded to let us experience something very old,” Miss Rosebud said. “I didn’t believe that a woman in our time could be persuaded to do anything.”

“Your remark is correct,” the director said. “There’s also something strange involved in this. According to what I’ve heard, an odd ancient poet has affected the artist.”

“Oh, what do you say?” Miss Rosebud exclaimed, drawing herself halfway up from her comfortable seat. There was an expression in her eyes that could have given an ancient writer reason to write something about the suffering of rejected love.

“I’m only telling you what I’ve heard,” the director added very carefully.

“So-o! Little Ozodes has dealings with a poet!” Mrs. Sharpman exclaimed. “Yes, as far as I have heard, she is supposed to marry a tempest-man, and the year of probation will soon be over.”

“Yes, indeed” the little miss put in. “His name is Oxygen, that I know, and he’s said to make quite excellent rain squalls. There can’t be much left of the year of probation. Oh, that’s bad behavior of Ozodes. That’s something the tempest-man should know, or what do you say, Mrs. Sharpman?”

The two ladies eagerly began whispering. Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar smiled, but it was a smile that in the novels of the past was called a “sinister smile.” Such phrases were not used in the 24th century, but the phenomenon still existed.

“Do you know Miss Rosebud?” asked an older man sitting near the ladies, and he turned to a lady sitting beside him.

“Oh yes! A little,” she answered.

“Is it true that she likes the author of The Last Locomotive?”

“I’m sure it’s true, but her love is not reciprocated. From what I hear, the poet loves someone else and cannot come to terms with little Rosebud’s modern views.”

“I’ve been told...”

“Hush! There’s Ozodes. How beautiful she is!”

A hum of approval went through the hall. A large number of men hastened on to the concert lady and handed her thick bundles of paper. That was the habit of the day to show enthusiasm. Applause had since long gone out of fashion. Flowers were also considered unserviceable.

Not a single laurel leaf existed any more. All bay trees had been stripped in the past centuries and no longer existed. People had used up the trunks and the branches for burning incense for young artists. Now they gave bundles of paper: stocks, bonds and other securities.

Much to the surprise and amazement of those present, a man stepped up to Aromasia and handed her some flowers. She smiled kindly at him, maybe even in a kinder way than she had smiled at all the men bearing paper. She even gave him her hand. The connoisseurs looked at each other, shrugged and shook their heads.

“But look!” Mrs Sharpman-Fulmar exclaimed. “I think it was that crazy poet. What a scandal!”

Miss Rosebud was completely pale. She said nothing, but her eyes “spat fire,” as the authors of old expressed themselves.

There was another person in the hall, who, though not exactly spit-firing, at least looked darkly upon the presentation of flowers and Aromasia’s smiling expression of thanks at the deliverer. That person was Oxygen.

“What is the fool’s purpose?” he murmured. “And why has Aromasia called her new composition The Seasons? It smells like old-fashioned romance. And I’ve not been notified in advance. Hm!”

Aromasia had nevertheless sat down at her ododion. The scent-artists assisting her filled their places, each of them with a smaller ododion. It was a complete concert: big band, as they said in the past. The ododion-insets were already entered into the instruments. They were always manufactured at the big central-laboratory at the former Nybrohamnen, the same place, where the Royal Academy of Music had its house some hundred years before, but the manufacturing was done according to Aromasia’s own instructions.

Everybody’s nostrils expanded, but the conversations continued without hindrance. It was one of the advantages of these scent concerts that one did not have to maintain silence. The function of the olfactory sense was not restrained by the buzz that went through the hall during the concert.

Many were surprised at the topic the artist had chosen and it was with a certain distrust that the audience began scenting the first movements, but the distrust was turned into confidence by the taste and capacity of the artist and passed into delight at her genius.

To begin with, they scented the fragrance of tender grass and of the first flowers of spring, sweet, apprehensive scent-chords that filled the mind with fresh thoughts and new life and seemed to break with everything old and antiquated and point towards a joyful future. This was the season of innocence, foreboding and hope. Then one was taken through a succession of scent-transitions into the rich abundance of summer.

The artist charmed out of her piano scents of new-mown grass, of strawberries and of the flowers special to the season. People enjoyed these scents and felt the power and happiness of summer run through their whole being.

“Oh, this is pleasant, this is lovely, this is sweet summer!” many exclaimed in the hall and several people hurried to the artist to present her with even more securities.

But then there were scents that were felt to be somewhat suffocating.

“We’re in the dog days!” people panted in the hall, mopped beads of perspiration off their foreheads and yearned for coolness.

“Hot, but brilliant!” Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar explained.

“Much too stifling!” Miss Rosebud exclaimed. “I think I’ll leave.”

But the powerful summer scents gradually subsided; others, less expressive, perhaps less fragrant, replaced the former scents. There was something withered and sad that caused gloomy autumn-thoughts, but soon one felt a strong scent of wine and the odor of several fruits. They counteracted the former scent but passed into a strong scent of alcohol followed by more and more strange scents and ended with grave-scents that aroused shudder and dread.

The women covered their mouths with their handkerchiefs and the men shrugged their noses while performing disgusting facial expressions.

“This is horrible!, Miss Rosebud declared.

“Oh, it’s brilliant,” the director said. “I am thinking of magnificent orders for mourning attires or at least a thousand winter coats.”

But the masterly odoration ended in a few comforting scent-chords, where some of the first spring movements were repeated, rather fainter, to be sure, and somewhat undefined, but they nevertheless enticed more satisfied expressions on the faces of those present.

With that, the concert was over. There were no other numbers that evening. The smellers showed their appreciation of the concert by handing the artist hundreds of shares in the best business, handicraft, and banking companies.

“What a fuss!” Miss Rosebud said.

“Look, there’s the crazy poet again!” Mrs. Sharpman-Fulmar exclaimed.

“Another scandal,” the miss declared.

“Yes, in the name of morality we should execute our agreement,” Mrs. Sharpman said.

“And that immediately,” the miss added.

To be continued...

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk