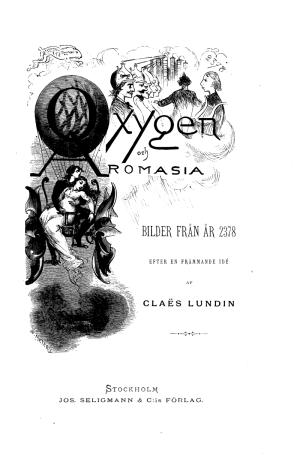

Oxygen and Aromasiaby Claës Lundintranslated by Bertil Falk |

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 appeared in issue 256. |

|

Chapter 2 The Scent Piano |

Inspired by the German philosopher and science fiction writer Kurd Lasswitz’ novel Bilder aus der Zukunft (“Pictures from the Future”), the Swedish journalist Claës Lundin (1825-1908) created the novel Oxygen och Aromasia, “pictures from the year 2378” — a date exactly five centuries in the novel’s future. Bewildering Stories is pleased to bring you this classic of early modern science fiction in Bertil Falk’s translation.

Aromasia sat down in one of her tastefully decorated rooms in front of a small and beautiful household furnishing, similar to the ancient upright pianos.

Aromasia sat down in one of her tastefully decorated rooms in front of a small and beautiful household furnishing, similar to the ancient upright pianos.

She opened the artistically ornamented lid and let her fingers run over the keyboard. At once a fine scent spread through the room. That scent was enhanced into the most powerful of fragrances as the artist began to play one of Riechmann’s emotional odorants.

The instrument she played was an ododion or a scent piano of the kind invented by the Italian Odorato in about the year 2100. With progress in chemistry, it had later been considerably improved.

The ododion Aromasia played was made by the famous scent piano company in Mora, the old parish by Lake Siljan in Dalecarlia. The company had begun by making wall clocks. Later it produced sewing machines and after that it manufactured phonographs. Ultimately, it proceeded to making scent pianos, perhaps the most natural handicraft for the locality.

Aromasia’s scent piano had a fairly wide scope, stretching all the way from the lowest scent in the scale —the heavy scents of soil and mud — up to smell of onion, a very fine scent-tone that was not discovered until the year 2369. Every time a key was pressed, a corresponding gasometer opened and the instrument made provision for the increase, spread and subduing of different scents as well as their co-operation with harmonious sweet smells.

The future music that appeared as early as in the 19th century had in the next two centuries developed to such a degree that it at last reached such a level of perfection that the ear could no longer endure more of the same. It happened thanks to the phonograph.

The famous Richard Wagner, the inventor of the music of the future, had pounded the human eardrums in such a powerful way that they in the end no longer were capable of receiving any impressions. Through the means of the phonograph, his disciples had sent trumpet blasts all over the world. For a long while, mankind was stone-deaf, and the ear was ultimately considered a superfluous body part.

It was at that point that art lovers and chemists, who as early as the 21st century combined their efforts and turned their attention to the nose, which had been ignored for a long time. In later centuries, the delicacy of the organ of smell had not been developed. It had rather retrogressed as a result of nicotine.

But why could that not be changed? None of the other human senses has such an impact on the capacity of thinking as scent. Therefore the next logical step was to make the most of this sense through the means of art.

With great thoroughness they set out to make observations about the oddities and effects of the scent. At first empirically and then theoretically they found the laws of harmony and disharmony in the olfactory sense. Chemistry produced the necessary aromas at increasingly less expense.

And then, after the ododion had begun its career as an oddity, it began to be used in the service of art and obtained a foothold in families. That was the end of music.

The first scent masters were Naso Odora, then Stinkerling, Mrs. Noseenius, Riechman and the parents of Aromasia, Mr. Scentman and his wife Mrs. Ozodes. Aromasia’s mother was born in Greece, where she was courted by her husband-to-be, thanks to his highly developed sense of smell.

All these people have produced ododion compositions that can easily be compared with the audidtory works of the greatest musicians. Soon the ododion was as widespread as the piano had been five hundred years before. But ododion playing was soon up to the same kind of mischief as piano playing had been in the past. The daughters and sons of the house absolutely had to learn how to create pleasant perfumes. However, very often the neighbors complained about abortive scents. People moaned as much about suffering noses as they in the past had lamented cruelty to their ears.

But Aromasia Doftman-Ozodes was an artist in the full sense of the word. Her scent chords were irresistible. Even as a child, she had achieved surprising scent compositions. They were of course sometimes discordant, but they were also rather often of a kind where dissonances resolved into the most sweet-scented harmonies. She had been considered a wonderful scent artist since her early childhood.

When she was ten years old, she permitted the public to smell a scent symphony — or an odorant — of her own composition. It met with frantic applause, and she was immediately employed as an infant prodigy. With that position went an annual allowance of one thousand francs, in the universal coin-language of the 20th century. It was indeed a small grant, but nevertheless an evidence of the wish of the public administration to promote the wonder child’s development.

Indeed, Aromasia made surprising progress. At the age of fifteen, she undertook an extensive art journey and let herself be scented at the foremost odortoriums on all five continents. For a single concert evening she could earn one or two hundred thousand francs. And now that she had reached the age of two decades, she possessed a fine fortune, which she herself administered. Every week it grew substantially, thanks to clever investments on the stock exchange.

Besides her art, she had thoroughly studied the higher science of financial operations and was even awarded a doctor’s degree by the world-famous faculty of finance in Gothenburg, an honor that was also shared by a large number of young ladies of the 24th century.

Femininity did not suffer from either art or finance. Aromasia was a charming a girl, as her grand-aunts had been in their youth during the past century.

However, Aromasia seemed most charming as she sat by her scent organ and permitted her rich imaginative power to put together the most wonderful odours. In so doing, she painted more lively, powerful and clear sensory pictures than those of any of the ancient tone painters.

It was just such a scent-painting she was busy with when she heard someone knocking at the window. Rapidly, she looked up and found that an air-bicycle had lowered itself down through the narrow opening of the backyard. Now it was hovering outside her room. Cheerfully, Aromasia nodded, got to her feet from the ododion and opened the window.

“Aromasia!” the visitor exclaimed. He was a man of about twenty-five years or perhaps more near thirty. “I have good news.” He attached his bicycle to the window-hatch, shook hands with Aromasia and without being asked to do so he sat down in one of the comfortable lounge-chairs.

“Do you bring some new fragrance?” the girl asked with enthusiasm.

“Not this time,” the newcomer replied. “This morning I was in Gothenburg and there I heard they’re considering electing you a member of the Scandinavian parliament.”

“Me!” Aromasia exclaimed and she almost looked scared. However, that expression lasted for only a moment. She quickly regained her usual frankness and added, “Well, why not? I’ve been of age for two years now. But perhaps my art would suffer from work in the parliament.”

“I don’t think so,” opined the young man. “With the easy means of communication of our time you can bike to the west coast in a couple of hours and return every day. The physical exercise in the air would do you good. On the way you can think out a new odorant.

“In Gothenburg you’ll join the business of the parliament. There you can continue with your art work, which is a meritorious activity for your country and for mankind. And you’ll still have a lot of free time.

“The way of the parliament is not as it was in the past at the sessions of the Riksdag. You know that thanks to engineering, new inventions have constantly simplified and facilitated the great machinery of parliament. Just think of the voting machines! How much faster and reliable they work as compared to those of former centuries!”

“You’re right,” Aromasia put in. “But it’s not decided that I’ll be elected. I guess that I must have competitors.”

“It’s true! And of both sexes, but they need a young and prominent artist, for they are the ones who better understand the more complicated calculations of finance. It’s the constituency of no less a place than Majorna that wants to elect you. Just think of it: the beautiful and respected Majorna, this ancient residence of wealth! It’s an honor for a young smeller, an honor which...”

“Oh, dear, dear Apollonides,” Aromasia interposed the swelling flow of words. “You’re a poet and now your power of imagination entices you to exaggerate.”

“Miss Aromasia,” the young man answered. “It makes me proud that you consider me to be a poet, but I’m above all your friend, your true and most affectionate friend. Why can I not exchange that friendship for something more pleasing? Why are you always that same inexorable, the same...”

“Come, come! Calm down, my friend,” Aromasia exclaimed. “Now you’re relapsing into the sentimental routine of centuries past. Can’t friendship be enough for you? Friendship is sufficient for many, but love is one and indivisible!”

“Then give me the one and indivisible!” the poet cried out with an expression of great passion.

“No, you know that I’ve already given away my love. It is owned by Oxygen.”

Aromasia once more sat down at her ododion, while Apollonides with heartbroken eyes looked at the wall of the house on the opposite side.

Unhappy love was expressed in the 24th century in just about the same way as it had been five hundred centuries before. In the 19th century, the poet Apollonides would have been considered an insufferable idealist as well as an eager romantic.

As a matter of fact, even in his position in the 23rd century, he readily dreamed himself back to the poetical period of the steam engine, to the days when people still had to look up to the mountains. He despaired of the power of poetry in an age when calculating reason was idolized, and he praised the epoch that was called the Newer Middle Ages, when — in the 19th century — one still heard about miracles and table-turning and spiritism were still in full swing.

“It was a wonderful time,” he would say. “Why have we now lost our ability to hear spirits knocking?”

But then he had once more turned his attention to the present and done service in the Scandinavian parliament as a poetry mechanic of the big voting mechanism. When the parliament had its meetings in Gothenburg, the capital, the poet/mechanic shared his time between that city and Stockholm, which — out of an objectionable poetic habit — he considered the actual abode of “intelligence,” as they said in the past. In Scandinavia, Stockholm shared this distinction with Copenhagen. Quite evidently, the young poet had very outdated opinions.

“Do you still think of your old steam power poetry?” Aromasia asked and turned to Apollonides.

”Oh, no, wonderful Aromasia,” the poet exclaimed and once more he spoke the language of his own age. “I think of you, the greatest odorist of this century. You are the one, who sets my brain cells swinging. It’s for you that every nerve fibre of my spinal marrow is in motion. As the mead sighs for the sun’s rays, when the morning air satisfied with steam has settled on the scenery, in the same way the fine mucous membranes of my organ of smell tremble for the scents of your ododion.”

That was the way a romantic expressed himself during the 24th century, but Aromasia found his oration poetically too exaggerated. “My friend,” she exclaimed even as her fingers continued toying with the keys, “you forget that we no longer live in the period when flattery was a way of influencing women. If I did the right thing, I would let Oxygen send a shower to rain on you.”

“You’re cruel, Aromasia! But I don’t fear anything like that. The living power of my warm blood shall disperse the water molecules.”

“We’ll see about that. Besides, you cannot be unaware of how you exaggerate. Your flatteries sound like mockery. I know my weakness very well, and I know that I can’t reach the ideals my nose is striving towards. I can never reach Riechman’s depth of thought. Just scent this simple transition from three kinds of aromas through half a minor scent to end-ozodien. How much is in that simple chord! Power, contempt for death, strength, the whole history of the invention of the electro-mechanical speed vehicle, the greatness of man, the rumbling of thunder and even the separate parts of the 1980 comet’s orbit. But it is, to be sure, only a Richard Riechman who can put together such a thing.”

“Oh, you’re too modest. I know your magnificent odorat The Seasons. And have you not portrayed on your ododion Materialism Conquering Criticism and The Completion of the Nicaragua Canal?”

“They were only vague attempts. But when will that master emerge who creates the great scent drama of the future? Riechmann isn’t eloquent, though he’s the greatest scentmaster. Oh, why are you not a scent artist, my friend?”

“Because I’m only a poet, a poor poet. But our ideals should not be sought in the future. Let’s turn back to the past.”

“Don’t mention it... maybe you want to talk about a Tegnér, an Oehlenschläger, a...”

“No, not that far back. But let’s think of the delightful The Last Phonograph! Behold, that’s poetry. Such a composition accompanied on ododion would be on a higher level than all poetic collections of our time and probably even of the future.”

To be continued...

Story by Claës Lundin

Translation copyright © 2007 by Bertil Falk